COMMENTARY: The true crime genre is slaying ratings while raising concerns

While true crime may be “killing it” at the moment, it is not the first time people have been fascinated by true stories of crime and scandal. Is society’s obsession with the genre cause for concern or is it just another harmless form of entertainment?

Serial killers and murder mysteries have infiltrated mid to late 2010s pop culture. However, this unsettling genre of storytelling did not start with podcasts and Netflix docuseries. The public’s fascination with true crime dates back to the 1800s with Charles Dickens and Edgar Allen Poe.

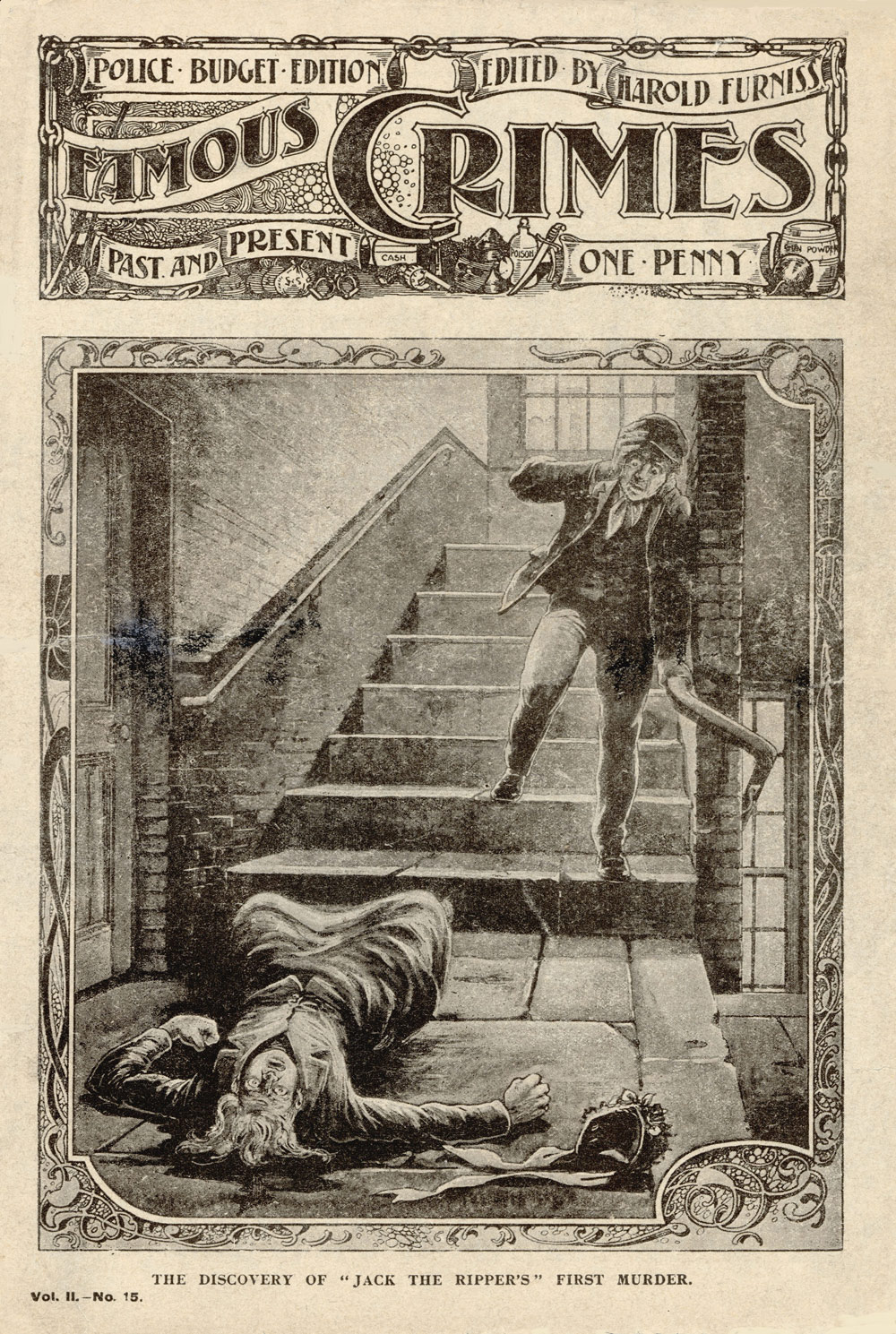

Society’s captivation with true crime has been around since the beginning of modern journalism. Murder pamphlets circulated England throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. These small pamphlets typically featured detailed accounts of murder cases accompanied by graphic illustrations. Penny dreadfuls, first published in the 1830s, told sensational stories about famous criminals and were sold for a penny each in Victorian-era Britain.

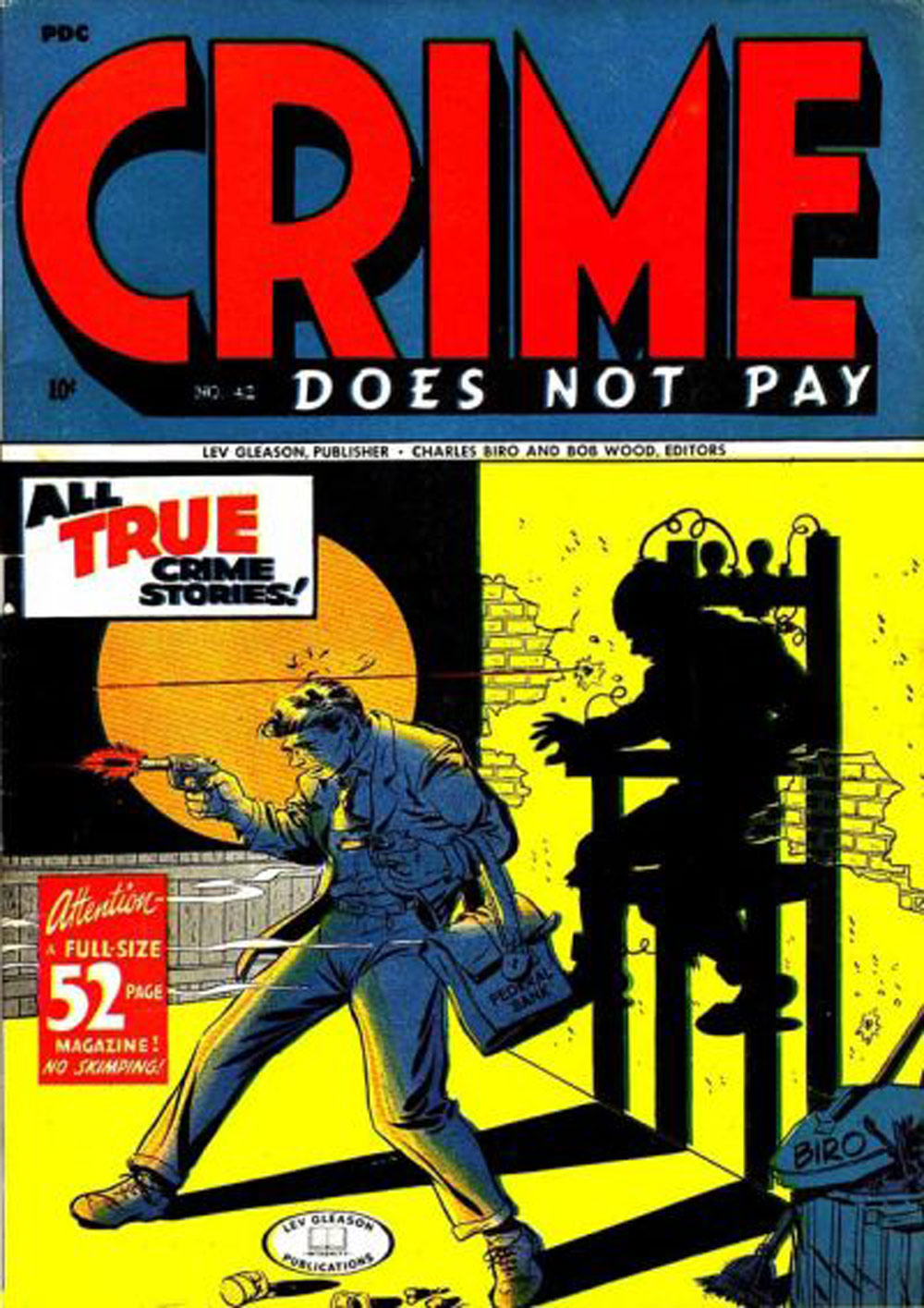

As the 20th century approached, literacy rates increased and crime stories shifted to newspapers, magazines and books. “True Detective” was the first true crime magazine and sold millions of copies in America throughout the mid-1900s. The popularity of true crime even spread to the comic book format in the 1940s with the new genre of “crime comics.”

Truman Capote’s “In Cold Blood”, originally published in 1965, arguably kickstarted American true crime literature. The book recounts the true story of four family members who were brutally murdered in a small Kansas farm town. Other famous novels that followed are Ann Rule’s “The Stranger Beside Me” about serial killer Ted Bundy and Vincent Bugliosi’s “Helter Skelter” about the notorious Manson murders. True crime quickly became a staple of American popular literature.

Television stations soon embraced the true crime trend, and programs such as “Unsolved Mysteries”, “Forensic Files” and “Dateline” grew in popularity in the ‘80s and ‘90s. In 2014, true crime went cable when HBO launched the American anthology crime drama series, “True Detective,” which told fictionalized stories based on true crimes.

The 2014 investigative journalism podcast “Serial” by Sarah Koenig was the fastest podcast ever to reach 5 million downloads. The award-winning podcast is currently the most downloaded podcast of all time and is said to have contributed to the recent resurgence of true crime entertainment. Subsequent podcasts followed in “Serial’s” footsteps and dominated top charts, including “Dr. Death,” “My Favorite Murder” and “Crime Junkie.”

No more than a year later, “Making a Murder” also gained a huge following and fueled the true crime fire. The American true crime documentary television series premiered on Netflix in 2015 and reached 19.3 million viewers in the first 35 days.

True crime is so popular these days that there are now annual conventions dedicated to the obsession, including Crimecon, True Crime Podcast Festival and Death Becomes Us True Crime Festival.

While the genre of true crime is a mainstream form of entertainment today, many ask the question, “is it normal?”

The concept of indulging in murder stories for fun sounds a bit twisted at first. However, experts compare society’s love for true crime to roller coasters, haunted houses and scary movies.

Nothing beats a good adrenaline rush. People like the physical feeling of being scared. Kidnappers, rapists and murderers trigger the most basic and powerful human emotion – fear.

Also, people like to solve puzzles and play armchair detective. Through films, print and podcasts, people have the opportunity to explore concepts that scare them most, all from the comfort of their home.

Psychologists also attribute true crime fascination with another very natural human trait – curiosity. Many people are drawn to the violence of murderers simply because their brains cannot comprehend a killer’s actions or logic. They want to understand the motivation behind such senseless acts of violence. Watching documentaries allows viewers to delve into the mind of a serial killer but from a safe distance.

While bingeing on murder podcasts and an entire series of crime shows may be an entertaining pastime for some people, it is not the case for everyone. True crime overload can lead to increased anxiety and nightmares, depending on the person. Some people may feel increasingly paranoid or depressed, which can affect their mental state and day-to-day life.

The chance that watching too many murder shows will lead to actually committing the heinous act, is slim to none. However, there are some consequences of true crime entertainment. Families and loved ones of victims may suffer from the retelling of their stories, potentially rehashing old wounds. This also brings up the controversy of using another person’s tragedy for entertainment purposes.

While the true crime entertainment industry may seem indecent, experts believe there is no cause for serious concern. Learning about true crime appeals to the innate human instinct for survival. Crime stories are about some of the most extreme aspects of human experience, and their unpredictable twists and turns are what keeps the audience pressing the “Next Episode” button time and time again.