EXPLAINER: Leading up to leap years

The evolution of the modern day calendar

As long as human beings have lived, they have sought to explore and understand the world they inhabit and to work toward creating a thriving existence. Useful for such an aim is the harness of time – or at least a conceptualization of it – as it allows for better planning, better communication, and better organization of human systems. Before there were leap years, months, weeks or named days, there was only lightness and darkness, starry skies, a changing moon and the cycles of weather over a vast land.

At some point, thousands of years ago, a person noticed the patterns in the winds and in the way the moon changed periodically. Thus, the structure of a year and the basis for a month entered human awareness. Over the course of many centuries, through observation, trial and error, humans have constructed and defined time-keeping systems that make sense of the natural world they occupy and leveraged them to create thriving societies.

Earliest Time Tracking

The earliest humans had limited ability to measure elapsed time or to predict and plan for seasonal change. These nomadic people relied on their observations of the moon, which allowed them to track days and months. Days were measured by observing the space between two nights, and months by the space between new moons. While these units of time were useful, the most critical time measurement for early human life was the length of a year as it relates to the changes in the seasons and affects crop production. The earliest people operated with only a conceptual understanding of a year with each passing harvest.

The First Calendar

Early settlers in the fertile valleys between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers formed some of history’s first cities. Ancient Mesopotamia is known as the “Cradle of Civilization” thanks to the various originations and advances that emerged from its societies. These ancient civilizations shaped cultures that were dedicated to specialized tasks and advancing their peoples’ organization. Observing and understanding the natural world around them was among these tasks. Motivated by the practical need for time-tracking and agricultural planning, Ancient Mesopotamians divided their year into seasons based on their phases of planting and harvesting.

Sumerians and Babylonians were the first civilizations to function using a modern calendar. They observed the lunar cycle, or the moon’s orbit around the earth, and used their observations to devise a calendar, which was comprised of 12 months based on lunar phases. The beginning of each month was evident by the first sighting of a new moon. In order to bring their calendar into alignment with the seasons of the solar-agricultural year, intercalary months were added to the calendar sporadically as deemed appropriate by decree.

Lunar and Solar Years

If it were not for extra months inserted into the calendar as needed, the Sumerian calendar would have become misaligned with the consistent and cyclical seasonal changes over the course of each year, complicating the natural rhythm of society and making agricultural planning and predicting quite difficult. Sumerians’ system of adding intercalary months to their calendar year as needed aimed to synchronize the lunar cycle with the Earth’s orbit around the sun, making it a lunisolar calendar, which helped their society to remain synchronized with agricultural seasons.

Graphic courtesy of dom1706 via Pixabay.

It is widely accepted that ancient Egyptians operated under a strictly lunar calendar until the first solar calendar was implemented at around the 25thcentury B.C. Based on historical evidence, Egyptians began astronomical observations of Sirius (the brightest star in the night sky), which allowed them to track and record Earth’s orbit around the sun by the star’s location in the sky each night. Using their observations and their tracking, they gaged that one full orbit of the earth around the sun took 365 days to complete. Thus, they created their calendar which comprised of 12 months with 30 days each and an additional five days at the end of every year to make 365 days total.

This ancient Egyptian calendar had a substantial flaw, though. Early Egyptians did not notice the mistake in their year-calculation for many centuries, but it was later determined that their estimation had come up slightly short. One full orbit around the sun did not take 365 days as originally thought; it was actually closer to 365 days and six hours before a year was truly complete. Although it may seem insignificant, the cumulative excess of time still results in the Egyptian calendar sliding backward through the seasonal cycles as the original lunar calendar also did. Only the Egyptian calendar did so much slower.

Ancient Roman Calendar

The early Roman calendar was attributed to Romulus, the first king of Rome. More accurately, ancient Rome’s first calendar based on historical lunar calendar systems which preceded it and borrowed heavily from the ancient Greek calendar. At the founding of Rome in about 753 B.C., the Roman calendar consisted of only 10 months and equaled 304 days. The estimated 61 days of winter remaining in the year were not assigned to any month.

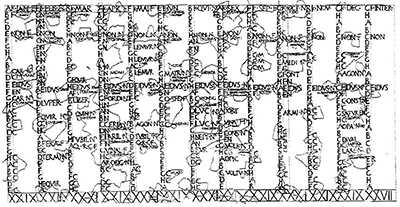

Photo courtesy of martieda via Pixabay.

Later, in 713 B.C. under the rule of Numa Pompilius, the Roman calendar underwent significant reform, as the calendar system had become increasingly essential to the flow of society. Rather than going unnamed, the winter season was divided into two new months and the Roman calendar year went from 304 days to 355. This system still resulted in a misalignment with the seasons, so extra days were added to some years intermittently based on political declaration. The disorganization of this calendar system led to centuries of confusion before further calendar improvement.

The Julian Calendar and the Invention of the Leap Year

Photo by efrye via Pixabay.

The Julian calendar, widely adopted under the rule of Julius Caesar in 45 B.C., was the closest system to solar year accuracy than any previous. Taking counsel from astronomer Sosigenes, Caesar added 90 days to the year 46 B.C. and began a brand-new calendar on the first of January, 45 B.C. Sosigenes advised the more accurate solar year length of 365 days and six hours and suggested the solution of the “leap-year.” An extra day would be added to February every fourth year.

Gregorian Calendar – The Calendar We Observe

While the Julian calendar was upheld and effective for many hundreds of years, by the 16thcentury it had become apparent that the original leap-year solution was not quite accurate either. Timely occasions such as the changes of seasons and the equinoxes were happening a full 10 days premature to their correct calendar dates.

Pope Gregory XIII commissioned an astronomer by the name of Christopher Clavius to calculate the flaw and formulate an adjustment. Clavius determined that the Julian inaccuracy totaled to three days in 400 years. He recommended that century years – years ending in “00—” should only receive the addition of an extra day if they are evenly divisible by 400. This new rule disqualified three would-be leap years from every four centuries which effectively resolved the problem and realigned the calendar. This solution was put into effect immediately and many other nations adopted it soon after. This Gregorian calendar is still the calendar we observe today in the United States.

Yet Another Calendar Improvement

Advanced technology and more exact measurements of our planet’s orbit have revealed the need for even further modification to the Gregorian calendar, although the slight inaccuracy would prove insignificant well into the future. Our present system skews our alignment by one extra day in every 3,323 years. One added rule solves the minor flaw: years that are evenly divisible by 4,000 will not be leap years. So, in approximately 1,980 years’ time, the month of February will end on the 28th.

Extra Day

A vast history of mankind’s plight to track time has led to here and now, 2020. Prehistoric humans who observed the moon and stars to better understand their world may have never imagined humanity’s advancements thousands of years later. This month’s calendar will include one additional day. February 2020 will end on the 29th.

Graphic by RioMike via Pixabay.