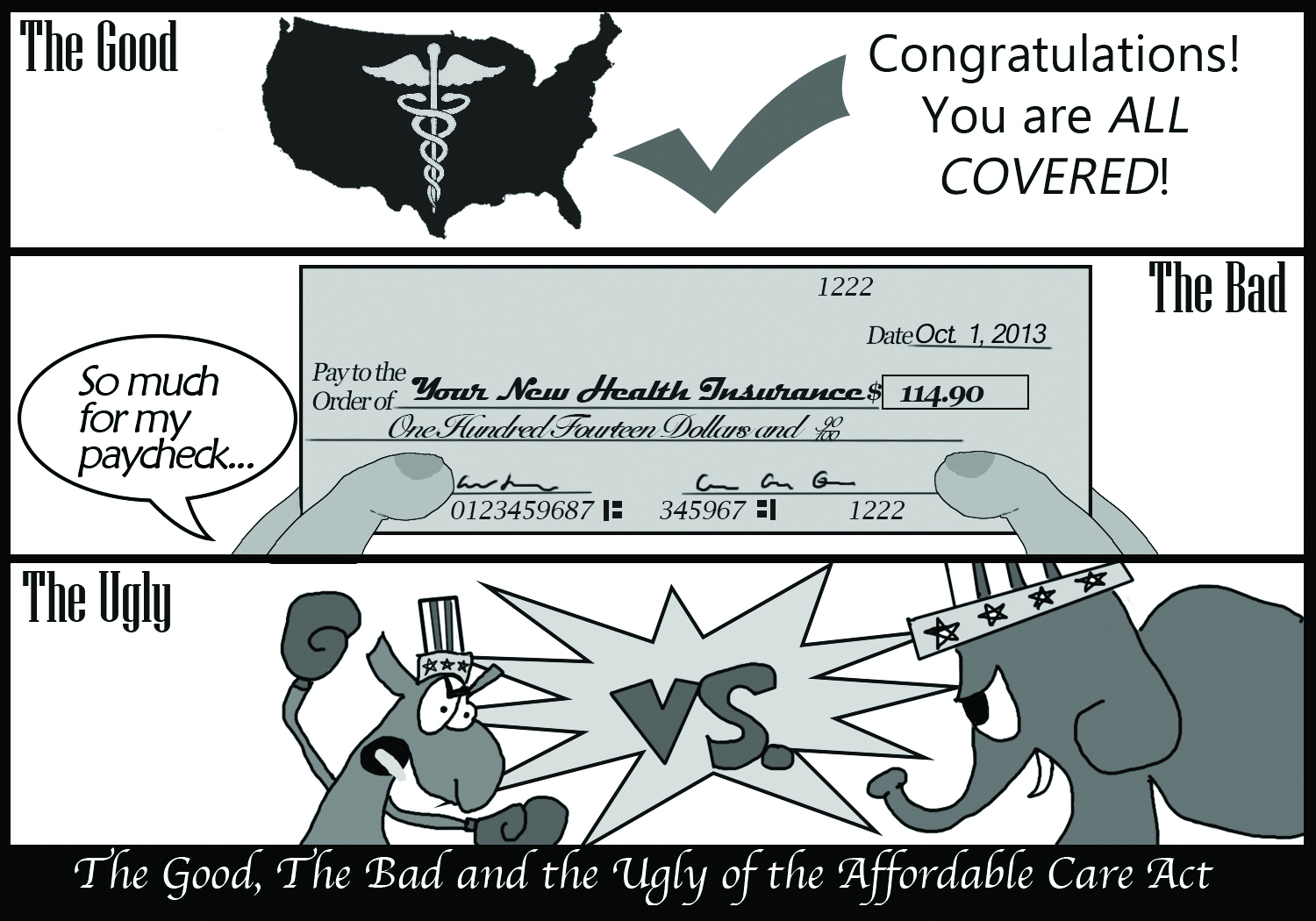

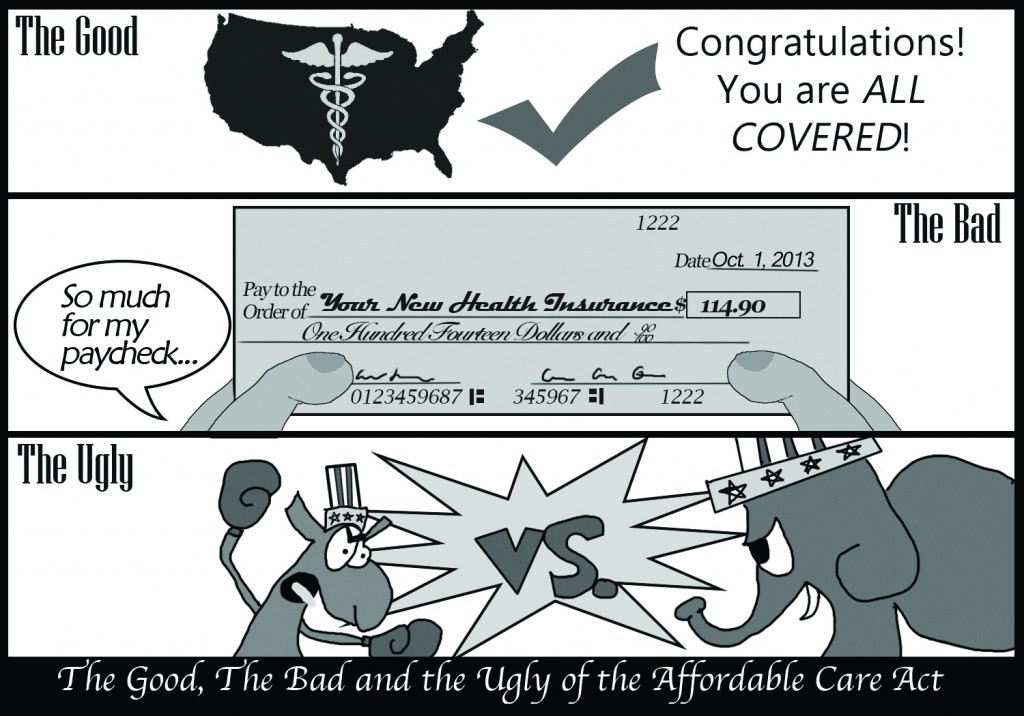

EDITORIAL: Affordable Care Act: Affordable for Whom?

The Nation Prepares For Healthcare Reform

American citizens witnessed the nation’s first robust healthcare plan since Medicaid and Medicare took center stage in 1965.

With a 219-212 House vote March 21, 2010, Republicans and Democrats reached a landmark agreement on a healthcare plan that could benefit all Americans.

President Barack Obama signed the healthcare plan into law March 23, 2010. Formally known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, it is commonly referred to as Obama Care.

Simultaneously, bipartisan parties unleashed campaigns both for and against the implementation of the new law. For every voice that argued this was the nation’s solution to the 49.9 million uninsured Americans, another voice argued against it. The bickering, coupled with an ambiguous 2,000-page document left many puzzled about how and when this would affect them.

Those intended to benefit most from the Affordable Care Act are those who are currently uninsured: minimum-wage workers, part-time workers and those with pre-existing illnesses. The new law’s intent is to help expand coverage to all people who need and want it, though exactly how the new law will benefit individuals is unclear.

Insurance rates for the state of Texas will become available Oct. 1. Meanwhile, the Kaiser Family Foundation website (www.kff.org) can produce an estimate based on the Affordable Care Act’s fundamental criteria.

If you live off of an annual salary that is either at the poverty level—in Texas that is $11,490 for a household size of one (www.familiesusa.org)—or up to 400 percent of that level—in Texas 400 percent above the poverty level is $45,960—and if the cost of the healthcare premium is more than 8 to 9.5 percent of your annual salary, the government will step in and help you pay for those insurance premiums.

The average single 26-year-old student in Texas making about $17,235 annually (150 percent of poverty level) will probably end up paying close to $114.90 per month for insurance.

While that seems like a good deal considering the average monthly premium paid by employees is in the $300 and up range, most students living paycheck to paycheck might still find the cost of healthcare somewhat hefty.

The other option is an estimated tax penalty of $95 per adult or 1 percent of your annual income, whichever is greater, and then that fee will continue to increase annually. In addition, those who choose the tax penalty will be responsible for the full cost of medical care, regardless of how high the amount.

In the coming months, you will need to do the math and decipher the new law to make an informed decision as to whether a tax penalty, or a monthly health insurance bill, will benefit you more.

The Affordable Care Act raises a few more questions than its direct benefits to uninsured Americans. Employers are also wondering what changes they will have to make and how that will affect their employees. Talks of cutting hours and workforces have surfaced, adding further concern to employees.

In addition, healthcare coverage for existing employees might be affected. There has even been talk of employers dropping existing coverage so that their employees can take on the task of finding health insurance for themselves.

Self-education is important in decoding the new law. Exactly how employers and employees will be affected by the Affordable Care Act will not be known until its full initiation next year.

While the intention of the new law is a good one—to make healthcare affordable and accessible to all Americans—the principal question is, affordable by whose standards?

The Affordable Care Act appears to be a step in the right direction, but there is much work to be done as it seems that those the new law is meant to reach, the lower- and middle-working classes, are still finding its goals unreachable.

The majority of uninsured Americans will tell you that the reason they are not carrying health insurance is not by choice, but rather because of a lack of options, so it does not matter if the new healthcare plan will cost $100 or $1000 a month; no extra money means no extra money.

Healthcare at a government-discounted price might sound like a great deal, but if the government is not careful, it may end up just another tax burden for its average-earning citizens.