REVIEW: ‘Miss Saigon’ misses the mark

Houston’s Hobby Center hosted the Broadway touring cast and crew of the musical “Miss Saigon” May 7-12. Originally opening in West End of London, “Miss Saigon” was created by Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boubill nearly a decade after their musical adaption of Victor Hugo’s “Les Misérables.” “Miss Saigon” was stated to be inspired by a photo of a Vietnamese mother giving her child away and influenced by Puccini’s “Madame Butterfly.”

“Miss Saigon” starts in the days leading up to America’s exit of the Vietnam War. Kim (played by Emily Bautista,) is forced to work as a prostitute by brothel owner, The Engineer (played by Red Concepcion,) and falls in love with an American soldier, Chris (played by Anthony Festa.) In the chaos of America’s sudden exit of South Vietnam, Kim and Chris are separated for three years. In this time, Vietnam is unified under the new communist regime, Kim gives birth to their son, Tam (played by Sarah Ramirez,) and Chris, thinking Kim is dead, remarries in the U.S. to Ellen (played by Stacie Bono.)

The performance and set

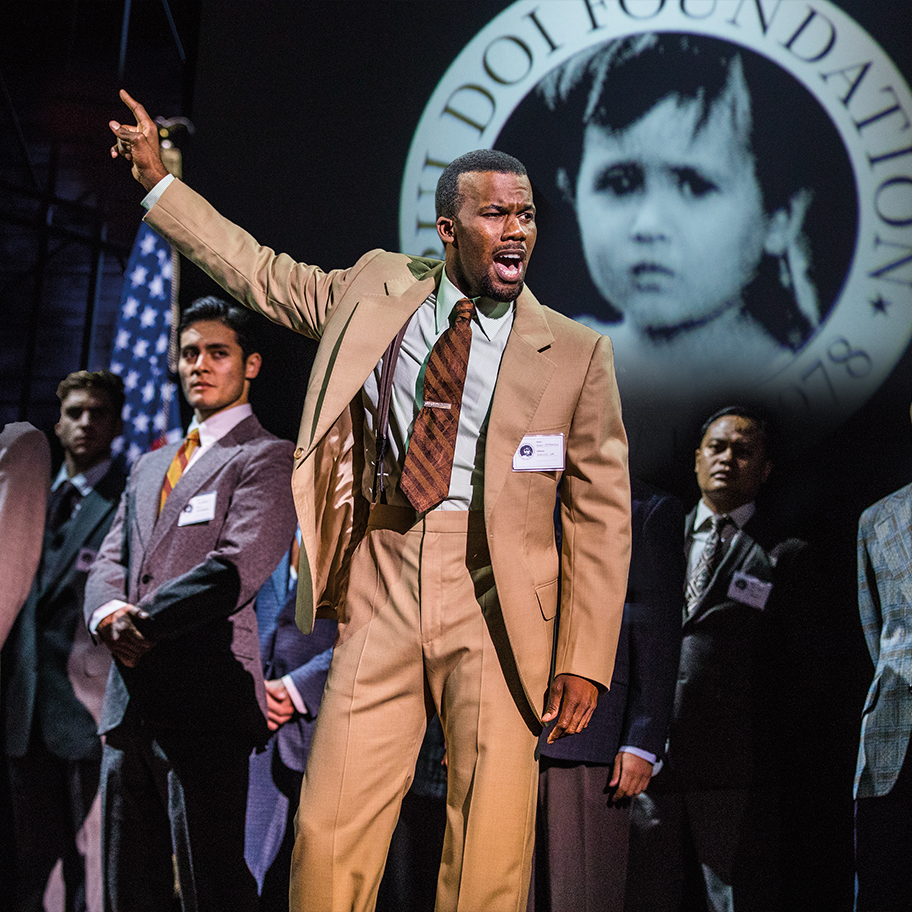

With the exception of a moment or two of awkward writing for characters Gigi (played by Christine Bunuan), lead prostitute before the arrival of Kim, and John (played by J. Daughtry), Chris’s fellow soldier, the performance by all of the cast was outstanding. There was a great blend of focus and movement by the cast with the help of the choreography, costuming and lighting. Almost every set was like a feast for the eyes as it left little to the imagination yet the stage did not feel cluttered or crowded when it was not supposed to be.

The show was roughly an hour behind schedule, but that was quickly forgiven when seeing the layers of height and depth on stage, intricacies of light and revolving set pieces and most notably, the military helicopter. Even though this story is set during wartime, the amount of strobe light flashes and gunfire could have been forewarned to allow for sensitive viewers to be on alert.

Though the helicopter is the big revealed set piece and probably the one requiring the most engineering, the real star was the gate of the U.S. Embassy. The gate took center stage as American soldiers “[got] the hell out” and the allied people of South Vietnam begged to be taken. Each side of the gate was shown at a time to draw emphasis on the character that was being followed. The back and forth created this sense of urgency supported by the screams, lyrics, music, smoke and lights.

Adaptation

This story is a product of its time but was more cringy than it had to be. The casting of Asian actors makes it appropriate surface level unlike the first run in The West End of London which was made up of mostly white actors in all the main roles with yellow face.

However, the production held steadfast making each Vietnamese character written to embody almost every Asian stereotype from the women being hyper-sexualized and/or submissive and the few men being predatory and/or greedy.

The existence of an online show guide, the motivation of the original writer and interviews with core people involved in the revival make it clear that the intention was to show the horrors of war and the respect owed to the people of Vietnam that were left behind – especially the mothers and children. This being said, it was not always clear in the production itself. That show guide was online, but never mention and nowhere on site for the audience goers at the Hobby’s opening night of “Miss Saigon.”

The only plot aspect that was kept and beneficial was the absence of a single antagonist. In many musicals, you can point at a person and two and call them complex, but they are clearly the “bad guys.” “Miss Saigon” stays true to life in that one person’s fate does not always have one finger to blame.

Responsibilities of the storytellers

Involving more women and people of color to behind the scene leadership positions will not bring it to “Hamilton” or “Allegiance” level of wokeness because those were created and first performed in the 2010s, but diversifying the leadership roles might yield better alternatives that sticking to closely to the original script. Older scripts are no longer an excuse for lack of diversity.

Without real full context, like the original writers and current show-runners have today, it is a disservice to tell the story as is. The gaps in information at best encourage viewers to do their own research on events that inspired the story or, at worst, be completely oblivious to the parallels and themes the creators try to make.

The audience’s reaction seemed to be the latter with a mostly white, upper-class audience grinning ear to ear and saying things like “I love a good tragedy.” The comments come off tasteless considering how the last scene plays out.

Americans’ uncomfortableness in discussing the horrors of contemporary wars results in an education system that either sanitizes or glosses over it all together. That attitude arguably contributes to the same mistakes being made today. This is part of the reason why this type of story still needs to be told in some form, if not musical.

The violence that caused the South Vietnamese people to flee and climb the barrier pleading to be taken with a failed ally is a reality of our time. The actions of Americans and North Vietnamese are not isolated events in history. The American interventions in South America and the Middle East have caused a similar rippling effect just like the story.

This miss education results in the public experiencing “Miss Saigon” and being sympathetic to Kim’s story without carrying that compassion to the real-life Kims of Syria, Yemen, or Guatemala.