EXPLAINER: Land acknowledgments begins conversation on local Indigenous history

Both UHCL and the Pearland satellite campus sit on the land of Akokisa, Karankawa, Coachuiltecan, and Atakapa-Ishak peoples. The Coachuiltecans span across south Texas and the Tāp Pīlam Coahuiltecan Nation’s headquarters is in San Antonio.

What are ‘Land Acknowledgments?’

A land acknowledgment, also called a territorial acknowledgment, is a formal statement recognizing the relationship between Indigenous nations and the land the statement is made upon. Traditionally shared at the start of an event or ceremony, people sometimes express acknowledgments with a plaque or page on a website. Advocates of this practice see this as the first step in reconciliation and as a way to honor the spiritual relationship Indigenous communities have with their ancestral land.

Land acknowledgments continue as a cultural practice of Indigenous nations. Outside of these communities, the practice is becoming more common with U.S. cultural institutions like universities, museums, libraries and performance spaces now acknowledge the land they occupy. However, in countries like Canada, New Zealand and Australia, people regularly interact with these statements. In Canada, for example, there are many public events like sporting events, performances and guest lectures, etc., starting with a land acknowledgment as part of the opening statements.

The increased visibility and representation of Indigenous stories in media have exposed many new audiences to the practice. At the 2020 Academy Awards, Māori and New Zealand director Taika Waititi included a land acknowledgment when introducing a segment. Minutes before that, he won the Oscar for Best-Adapted Screenplay for “Jojo Rabbit.” He stated, “I dedicate this to all the Indigenous kids of the world who want to do art and dance and write stories—we are the original storytellers.”

TWEET: At the 2021 Academy Awards pre-show, the President of the Academy of Motion Pictures Arts and Sciences David Rubin read a land acknowledgment.

Watching #Oscars pre show”s indigenous land acknowledgement . Is this a first time for the Oscars? #reconciliation pic.twitter.com/ojCxI2xCHH

— Shiral Tobin (@shiral) April 25, 2021

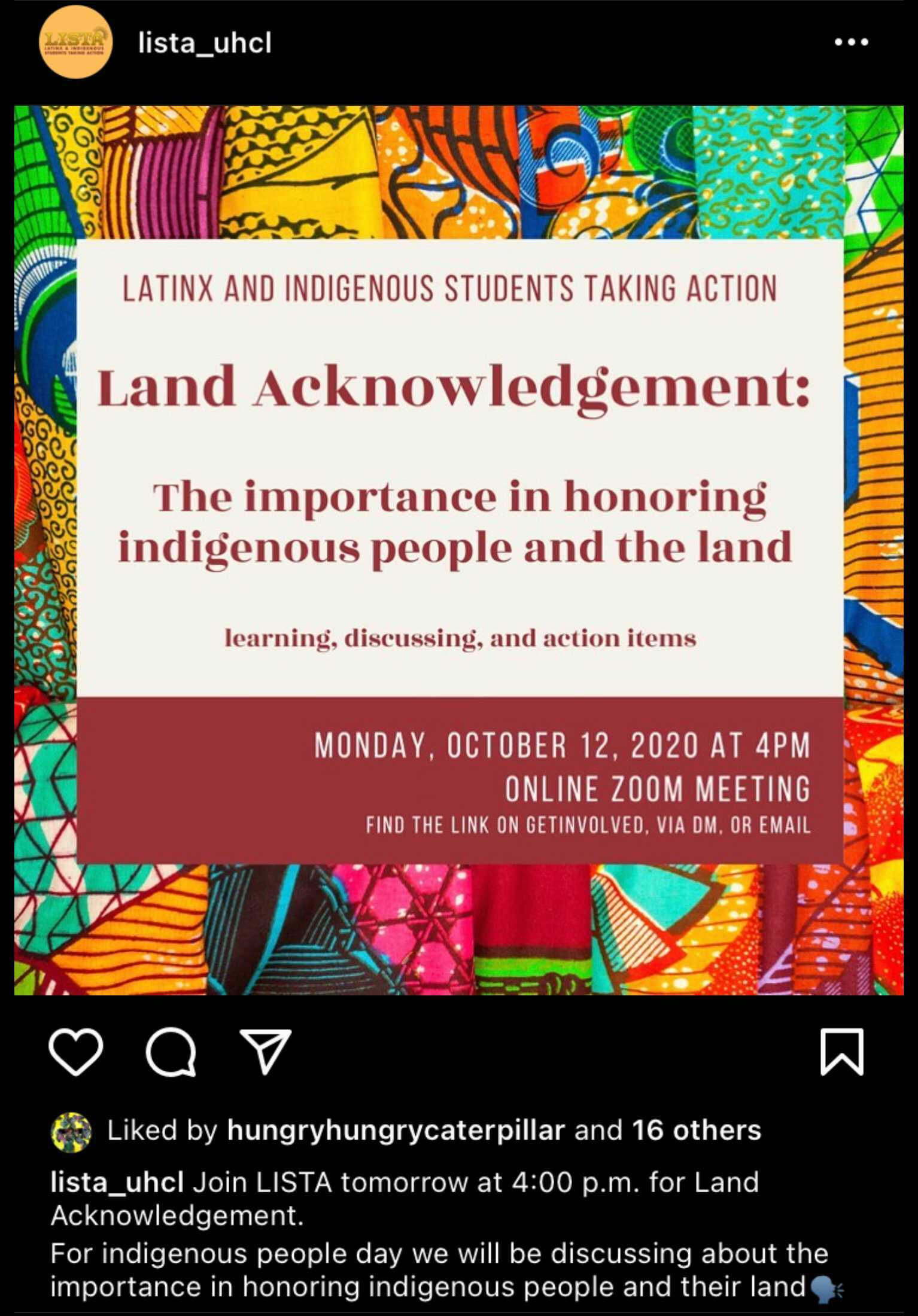

UHCL and regional higher education

UHCL has yet to host a land acknowledgment ceremony or a continued acknowledgment through official university channels. However, there are faculty and student groups on campus that have started these discussions. Since forming in 2019, Latinx and Indigenous Students Taking Actions (LISTA) organization start its meetings with a land acknowledgment. This began under the leadership of LISTA officers Erica Solis and Arturo Perez with the support of LLAS faculty Desdamona Rios, professor of social psychology, and Christina Cedillo, professor of writing and rhetoric.

After potential members experience a land acknowledgment for the first time at a LISTA meeting, current LISTA president Jacq Garcia, arts and design major says they come to the next meetings after researching the topic.

“These conversations are a good stepping stone,” Garcia said. “A lot of people just don’t know what it means to do a land acknowledgment. Some people think it is like a prayer or something, but that is not necessarily what it is.”

Outside of LISTA, the Student Government Association has begun to look into land acknowledgments and some UHCL faculty adopt them in various forms in their own practice. These forms of land acknowledgment exist in places like their syllabus and curriculum.

On the first day of class, Cedillo tells her students what her research is, where UHCL is located and where her ancestry derives from, but does not include a land acknowledgment in her syllabus. She then “encourage[s] them to talk about where their ancestors are from.” She sees this approach “as a way of inviting students to bring where they come from into the classroom.”

“Colonization has really affected BIPOC in certain ways that I think a lot of people just don’t know where they are from or who they are through their family,” said Cedillo. “People have been encouraged to strive for whiteness and in order to do that you have to eliminate your cultural history.”

In addition to people of color, those of European and/or Jewish ancestry have a history of changing their names to assimilate into mainstream/white society.

“Being a Latinx person of Indigenous descent, I have had to do a relearning of a lot of my own culture that has been lost over time,” she said. “I come from a family where people were deliberately encouraged to indigeneity leave behind and to try and assimilate as much as possible.”

The personal and professional mentors that helped Cedillo unlearn are Indigenous scholars from different nations. Cedillo stated that Native scholars will begin conferences and discussions with a land acknowledgment “as a way of acknowledging whose land they are one.” This practice goes back to pre-colonial America.

At the local level, the UH Main Campus Faculty Senate released a general acknowledgment in Spring 2020. The 2018 American College Personnel Association (ACPA) Convention began panels with land acknowledgments. Leading the ACPA 2018 convention, Melissa Jacob from Ohio State University wrote, “land is not just merely space that bodies occupy; it is a depository of culture, story, history and tradition” to those who questioned the need for these statements.

Outside of public institutions, private organizations and businesses in the Houston area have also started implementing land acknowledgments. The book publisher Six Foot Press and the Harris County Law Library both include land acknowledges and resources to learn more about those Indigenous communities. After opening a new building, the Houston Mennonite Church shared the statement displayed on a placard inside.

“We are renovating our permanent exhibit on Native American cultures and will incorporate our own land acknowledgment,” said Dirk Van Tuerenhout, curator of anthropology at the Houston Museum of Natural Science (HMNS.)

In a virtual event discussing HMNS’s John P. McGovern Hall of the Americas renovations, Tuerenhout described the guiding principles encompass a sentiment that Indigenous people are still here.

How to make a land acknowledgment

There is no template for a land acknowledgment. However, several organizations have provided “dos” and “don’ts.” Here are some key components gathered from the Native Governance Center, New York University’s LandAcknowledgements.org and the U.S. Department of Arts & Culture:

Do be sincere and use appropriate language

Use respectful language and consult with tribes on language.

Many resources stress the importance of using present tense because Indigenous people exist today. They also state that while writers should not be overly graphic, they should not “sugarcoat the past.” They suggest language like “genocide,” “stolen land,” “ethnic cleansing” and “forced removal.”

Cedillo warns against using a land acknowledgment in a spiritual sense, but instead to use it ceremoniously and in a personal way to foster community.

Outside of internet research, Cedillo, Tuerenhout and Garcia all stressed the importance of making those connections with local tribal communities including as part of the land acknowledgment process.

“Seek mentorship and seek Indigenous people’s insight,” said Garcia. “If you are doing it just for yourself and you don’t seek counsel from someone in the community, then who are you really doing it for?”

Do the research

“Find resources online that will tell you what land you are on or what land you are traveling to,” said Cedillo.

Websites like Native Land Digital’s native-land.ca can aid. Direct messaging this bot on Facebook with a city and state will let the user know the names of Indigenous groups from the area using Native Land Digital’s database. When finding the names, check several sources on pronunciation.

Cedillo suggested finding the local offices of the tribes, as they often encourage people to learn more.

“Even though it might be (for example) Cherokee Nation land now, it used to be a different people’s land before and they were pushed out by the government.”

Do not stop at a land acknowledgment

Although land acknowledgments are intended to serve as a starting point towards action, an acknowledgment alone is labeled as performative by critics. Long-term harm towards a community often provides no consensus about the next steps. Those that participate in the #LandBack movements demand public lands (like national parks) be returned to First Nations, while others are pushing for community investment as a form of reparations. All advocates stress the importance of land acknowledgments being a first step, not a last.

This sentiment is shared by both Garcia and Cedillo. Garcia said, “I think it is really important to research different organizations within your community or even at large.”

They suggested causes like helping women access reproductive health services and housing; raising awareness of cultural practices like danza azteca and raising awareness of missing Indigenous women across the U.S. and Canada.

“Get involved and if you are able to contribute monetary donations to these organizations,” Garica said.

“Being aware that the land on which we live was never ceded by the Native people is important,” Tuerenhout said.

“They were forcefully removed from it,” Tuerenhout said. “That is a historical reality and injustice. It is something we all need to learn more about and acknowledge. By making this acknowledgment, we, as a society, make the Native populations less invisible, more recognized. We acknowledge that they are very much ‘still here.’ A land acknowledgment is a first step in helping to grow awareness.”

UHCL adopting a land acknowledgment

Members of the UHCL community have expressed interest in a formal recognition.

Garcia said, “An event like graduation — if someone could take a moment to acknowledge the land, I think that would be huge.”

Cedillo, Garcia and other members of the UHCL community have expressed mixed feelings about the possibility of UHCL doing a land acknowledgment. The recurring concerns are that it would be a performative statement and would lead to nothing else.

“‘Are they ready for it?’ That is the real question,” said Garcia.

“Among native people, relationality is something that is really important,” said Cedillo. “Relationships are something that is enacted, not just spoken. So land acknowledgments are good because they remind us that there are things that we still need to learn about where we are at, where we are from and where we are going.”

Learn more

Articles and guides

- Know The Land Territories Campaign – Laurier Students’ Public Interest Research Group

- Indigenous Allyship: An Overview – Laurier Students’ Public Interest Research Group

- HONOR NATIVE LAND: A GUIDE AND CALL TO ACKNOWLEDGMENT – U.S. Department of Art and Culture

- #LandBack is Climate Justice – Lakota People’s Law Project

- NDN COLLECTIVE LANDBACK CAMPAIGN LAUNCHING ON INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ DAY 2020 – NDN Collective

Movies and online videos

- “Promised Land” (2016)

- “Gather” (2020)

- Land Acknowledgement – Molly of Denali (PBS Kids)

- #HonorNativeLand – U.S. Department of Arts and Culture

- Honoring Indigenous Cultures and Histories | Jill Fish “ TEDxMinneapolis – TEDx Talks

- We Are All on Native Land: A Conversation about Land Acknowledgements – Field Museum